25 Oct Doctor, what can I do to prevent prostate cancer?

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer among men. It is also one of the leading causes of cancer death among men of all races and Hispanic origin populations.1

For men diagnosed with prostate cancer, the question of what to do next is foremost in their minds. Surgery?Radiation?Wait to see how quickly the tumour grows? But somewhere in the midst of all the soul-searching, many inevitably wonder, ‘‘Is there anything I could have done to prevent prostate cancer in the first place?” Here is where your role as a family physician appears, making it important to learn to recognize the symptoms and increase an awareness around testing in your patients to prevent prostate cancer.

There are four well-established risk factors for prostate cancer:

- Increasing age: About 6 cases in 10 are diagnosed in men aged 65 or older, and it is rare before age 40.2The average age at the time of diagnosis is about 66.

- Ethnic origin: Prostate cancer occurs more often in African-American men and Caribbean men of African ancestry than in men of other races. African-American men are also more than twice as likely to die of prostate cancer as white men. Prostate cancer occurs less often in Asian-American and Hispanic/Latino men than in non-Hispanic whites. The reasons for these racial and ethnic differences are not clear.

- Geography: Incidence of clinical PCa differs widely between different geographical areas, being high in the USA and northern Europe and low in South-East Asia. However, if Japanese men move from Japan to Hawaii, their risk of PCa increases. If they move to California their risk increases, even more, approaching that of American men.3These findings indicate that exogenous factors affect the risk of progression from so-called latent PCa to clinical PCa. Factors such as the foods consumed, the pattern of sexual behaviour, alcohol consumption, exposure to ultraviolet radiation, chronic inflammation 4,5 and occupational exposure have all been discussed as being aetiologically important. 5

- Heredity:If one first-line relative has PCa, the risk is at least doubled. If two or more first-line relatives are affected, the risk increases by 5-11-fold.6,7This risk is further increased if the cancer was diagnosed at a younger age (less than 55 years of age) or affected three or more family members.

Among single components of the metabolic syndrome, only hypertension and waist circumference >102 cm was associated with a significantly greater risk of PCa, increasing it by 15% (p = 0.035) and 56% (p = 0.007), respectively.8

Hereditary factors are important in determining the risk of developing clinical PCa, while exogenous factors may have an important impact on the risk of progression.

Screening and early detection of prostate cancer

The American Cancer Society (ACS) recommends that men have a chance to make an informed decision with their physician about whether to be screened for prostate cancer. The decision should be made after getting information about the uncertainties, risks, and potential benefits of prostate cancer screening and the patient’s risk factors, age and life expectancy. The goal of cancer screening is not just to detect cancer, but also to prevent morbidity and mortality.

Informed men requesting an early diagnosis should be given a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test and undergo a digital rectal exam (DRE). The interval for follow-up screening depends on age and baseline PSA level. This could be every 2 years for those initially at risk or postponed up to 8 years in those not at risk. There is no question that screening can help find many prostate cancers early, but there are limits to the prostate cancer screening tests used today.

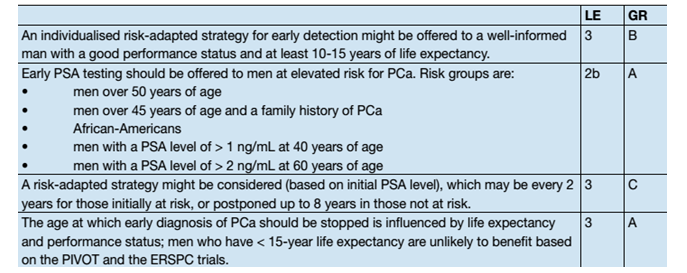

Guidelines for screening and early detection9

Can prostate cancer be prevented?

Many of the risk factors stated above cannot be controlled. But based on what we do know, there are some things you can advise that might lower your patient’s risk of prostate cancer.2

- Several studies have suggested that diets high in certain vegetables (incincluding tomatoesabbage, broccoli, cauliflower, soy, beans, and other legumes) or fish may be linked with a lower risk of prostate cancer.

- Studies have found that men who get regular physical activity have a slightly lower risk of prostate cancer.

Adequately educating patients about prostate cancer and advocating protective factors may lower their risk of prostate cancer.

References

- cdc.gov/cancer/prostate/statistics

- American Cancer Society Guidelines for the Early Detection of Cancer

- Breslow N, Chan CW, Dhom G, et al. Latent carcinoma of prostate at autopsy in seven areas. The International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyons, France. Int J Cancer 1977 Nov;20(5):680-8.

- Nelson WG, De MarzoAM, Isaacs WB. Prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2003 Jul;349(4):366-81.

- Leitzmann MF, Rohrmann S. Risk factors for the onset of prostatic cancer: age, location, and behavioral correlates. ClinEpidemiol 2012;4:1-11.

- Jansson KF, Akre O, Garmo H, et al. Concordance of tumor differentiation among brothers with prostate cancer. EurUrol 2012 Oct;62(4):656-61.

- Hemminki K. Familial risk and familial survival in prostate cancer. World J Urol 2012 Apr;30(2):143-8

- Esposito K, Chiodini P, Capuano A, et al. Effect of metabolic syndrome and its components on prostate cancer risk: meta-analysis. J Endocrinol Invest 2013 Feb;36(2):132-9.

- N. Mottet et al, Guidelines on Prostate Cancer, European Association of Urology 2015