25 Oct Gastroesophageal reflux

Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is an involuntary retrograde passage of gastric contents into the esophagus with or without regurgitation or vomiting. Most episodes of reflux in healthy individuals last less than 3 minutes, occur in the postprandial period and cause few or no symptoms. Sometimes infants (0 to 12 months) spit up but do not have symptomatic reflux. About 50% of healthy 3- to 4-month-old infants spit up at least once a day, known as “happy spitting.” Most infants with asymptomatic GER grow normally and the condition often peaks at 4 months and resolves by 12 to 18 months of age.1

Incidence

About 70-85 % of infants have regurgitation within the first 2 months of life, and this resolves without intervention in 95 % of infants by 1 year of age.2

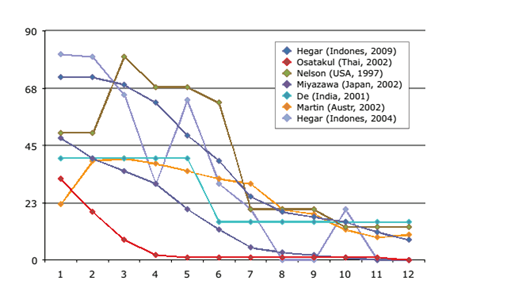

Natural evolution of regurgitation in health infants3

Another cohort study was performed in 216 healthy Thai neonates with a followup for 1 year. An infant who regurgitated at least 1 day per week was considered to have reflux regurgitation.4(To answer queries, pls refer to abstract at the end of this document)

In 145 infants, the prevalence of reflux regurgitation peaked at 2 months at 86.9% and significantly decreased to 69.7% at 4 months, 45.5% at 6 months, and 22.8% at 8 months. At 1 year of age, only 7.6% of infants still had reflux regurgitation. Most Thai infants with gastroesophageal reflux had mild symptoms: 90% of them regurgitated only one to three times per day. 4

In conclusion, the prevalence of reflux regurgitation in Thai infants was highest at 1 to 2 months of age; with most infants becoming symptom-free by 6 months.

Symptomatic GER can result in some feeding difficulty or refusal, irritability, and back arching.

Management of GER

Experiences from South East Asian studies suggest that a careful history and physical examination, with attention to warning signs, is generally sufficient to establish the diagnosis of uncomplicated GER.3

Effective parental reassurance, positional treatment, dietary recommendations and education regarding regurgitation and lifestyle changes are usually sufficient to manage infant reflux.2

North American Society for pediatric gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) and European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) practice guidelines recommend:5

General measures in infants:

Positioning:

- Upright’ position – more reflux

- Prone: less GER, difficult to apply, uncomfortable, higher risks of SIDS, NOT recommended

Diet:

- There is evidence to support a 2 to 4 week trial of an extensively hydrolyzed protein formula in formula-fed infants with symptoms suggestive of reflux disease.

- Antiregurgitant (AR) formulae containing processed rice, corn or potato starch and bean gum

General measures in older children & adolescents:

- Reduce weight in obese patients

- Avoid large volume meal and late night eating, quit smoking, avoid chocolate and alcohol

- Low-carbohydrate diet reduced distal esophageal acid exposure and improved symptoms in obese individuals

Pharmacotherapy

The guideline recommends step-up and step-down therapies. Step-up therapy involves progression from diet and lifestyle changes to H2 -receptor blockade medications (eg, ranitidine) to proton pump inhibitors (eg, omeprazole) Both classes of acid antisecretory agents have proven safe and effective for infants and children in reducing gastric acid output.6

Acid-Suppressant Therapy5

- Histamine2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs) produce relief of symptoms and mucosal healing.

- Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are superior to H2RAs in relieving symptoms and healing esophagitis. When acid suppression is required, the smallest effective dose should be used. Most patients require only once-daily PPI; routine use of twice-daily doses is not indicated. No PPI is approved for use in infants younger than 1 year of age.

Prokinetic and Other Therapy5

- The potential benefits (i.e. reduction of reflux-related symptoms, in particular, regurgitation or vomiting) of currently available prokinetic agents are outweighed by their potential side effects.

- There is insufficient evidence to support the routine use of metoclopramide, erythromycin, bethanechol or domperidone for GERD.

- Since more effective alternatives (H2RAs and PPIs) are available, chronic therapy with buffering agents, alginates and sucralfate is not recommended for GERD.

Acid suppression and prokinetic medications have a limited role in the treatment of infants with regurgitation. They are not valuable in the treating children less than one year of age with uncomplicated gastroesophageal reflux (“happy spitters”)7

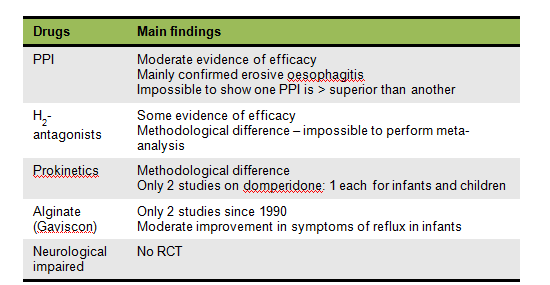

Cochrane Review of Drug Therapy in GERD 8

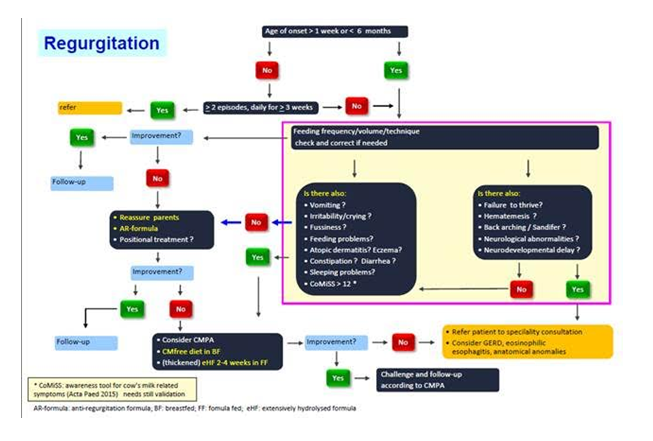

Diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm to aid in the evaluation and management of GER9

Summary

GER represents a common physiologic phenomenon in the first year of life. The distinction between this “physiologic” GER and “pathologic” GER in infancy and childhood is determined not merely by the number and severity of reflux episodes (when assessed by intraesophageal pH monitoring), but also, and most importantly, by the presence of reflux-related complications, including failure to thrive, erosive esophagitis, esophageal stricture formation, and chronic respiratory disease. The goals of medical therapy are to decrease acid secretion and, in many cases, to reduce gastric emptying time.

References

- Pediatrioc Gastroesophageal reflux Treatment and Referral Guidelines, Departments of Pediatrics at Carolinas

- Czinn SJ et al, Gastroesophageal reflux disease in neonates and infants : when and how to treat.Paediatr Drugs. 2013 Feb;15(1):19-27. doi: 10.1007/s40272-012-0004-2.

- BadriulHegar, Gastroesophageal reflux in infants Southeast AsianJtropMed public health, Vol 45 (Supplement 1) 2014

- Osatakul S et al, Prevalence and natural course of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms: a 1-year cohort study in Thai infants.J PediatrGastroenterolNutr. 2002 Jan;34(1):63-7.

- Vandenplas Y et al, Pediatric Gastroesophageal Reflux Clinical Practice Guidelines: Joint Recommendations of the North American Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. J PediatrGastroenterolNutr 2009;49:498-547.

- Hassall E. Decisions in diagnosing and managing chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease in children.J Pediatr. 2005 Mar. 146(3 Suppl):S3-12

- http://cursoenarm.net/UPTODATE/contents/mobipreview.htm?2/5/2129?source=see_link

- Cochrane Systematic Review 2014

- Vandenplas Y et al, Functional gastro-intestinal disorder algorithms focus on early recognition, parental reassurance and nutritional strategies.Acta Paediatr. 2016 Mar;105(3):244-52

J PediatrGastroenterolNutr. 2002 Jan;34(1):63-7.

Prevalence and natural course of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms: a 1-year cohort study in Thai infants.

Osatakul S1, Sriplung H, Puetpaiboon A, Junjana CO, Chamnongpakdi S.

Author information

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Epidemiologic studies in adults suggest that the nature of gastroesophageal reflux may differ among various ethnic groups. Until recently, there has been limited information concerning the epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux in non-Western children. The objectives of this cohort study were to investigate the prevalence of symptoms related to gastroesophageal reflux in Thai infants and to describe the clinical course of reflux regurgitation during the first year of life.

METHODS:

A cohort study was performed in 216 healthy neonates who attended the well-baby clinic of Songklanagarind Hospital between March and June 1998. All neonates were followed up, at regular well-baby clinic visits, for 1 year for reflux symptoms and clinical progress. Information concerning gastroesophageal reflux symptoms was obtained by interviewing the parents and from their diary records. An infant who regurgitated at least 1 day per week was considered to have reflux regurgitation.

RESULTS:

No infant with clinical features of pathologic gastroesophageal reflux or other reflux symptoms apart from regurgitation were seen during this study period. Of 145 infants in a 1-year cohort, the prevalence of reflux regurgitation peaked at 2 months at 86.9% and significantly decreased to 69.7% at 4 months, 45.5% at 6 months, and 22.8% at 8 months. At 1 year of age, only 7.6% of infants still had reflux regurgitation. Most Thai infants with gastroesophageal reflux had mild symptoms: 90% of them regurgitated only one to three times per day, and daily regurgitation was reported in a low percentage. Comparing infants with reflux regurgitation and those without, the standard deviation scores of body weight for age were similar. There was no significant difference in prevalence of reflux regurgitation between breast-fed and bottle-fed infants.

CONCLUSIONS:

The nature of gastroesophageal reflux in Thai infants differs from that in Western infants. The prevalence of reflux regurgitation in Thai infants was very high at 1 to 2 months of age; however, many infants became symptom-free by 6 months. The type of feeding (breast milk vs. bottle milk) had no influence on the prevalence of reflux regurgitation.